Caribs in Dominica

-

Profile

The indigenous Caribs (Kalinago) who are a minority in Dominica are unique in being the last community in the Caribbean that claims direct descent from the indigenous Kalinago who originally populated the entire region before the arrival of European colonizers.

There is some debate as to how many so called ‘pure’ Caribs remain, but a population estimated at about 3,400 people inhabits the 3,782-acre Carib Territory on the east of the island, of whom only 70 define themselves as ‘pure’.

The Carib Territory is governed by the 1978 Carib Act. Residents over the age of 18 are eligible to elect a Chief and six member Council of Advisors for a five year term as well as to elect a representative for the national parliament.

Kalinago-Caribs farm their land collectively and have also developed handicrafts for the tourist market. The Carib Territory is among the poorest districts in Dominica.

About 65 per cent of the Carib-Kalinago population are between the ages of 18 and 35.

School, water, and health facilities are available on the territory. Although these are essentially of a basic nature, they are similar to those offered to other rural populations in Dominica.

There is no secondary school in the Carib Territory, but there is a three-person police station generally staffed by Kalinago-Caribs.

Unemployment in the Territory is higher than in rest of the country and incomes are lower than the national average.

Historical context

Pre-Colombian

Today’s Caribs are the descendants of what was long considered to be male migrants from mainland South America, who ‘roamed’ the sea that bears their name, supposedly killing off the Arawak men and intermarrying with the indigenous Arawak women.

This model was based on the fact that up until the 20th century Carib-Kalinago men in Dominica spoke a language called ‘Carib’ and women supposedly spoke a different Arawakan language.

However what was once thought to be a separate Carib ‘men’s language’ that differed from the language of ‘conquered’ Arawak women’ is now considered to have been originally a pidgin trading vernacular used by Kalinago (island Carib) populations to communicate better with coastal Calibi (Carib-Kalina) of the South American mainland and the groups of the interior.

Modern anthropologists now identify both the island Kalinago populations and the language early French missionaries labelled as ‘Carib’, as being of long-term Arawakan origin.

Resistance fighters

The Kalinago (island Caribs) earned an early reputation among European colonizers for being very effective resistance fighters (see also St Vincent and Grenada). They kept Europeans away for nearly two centuries and became a sanctuary for regional indigenous groups escaping the invasion of their own territories.

France eventually claimed Dominica in 1635 and though Kalinago attacks prevented establishment of permanent colonies, the insertion of Capucine and Jesuit missionaries in 1642 was crucial for acquiring useful information on the ‘Carib’ language and way of life.

In contrast to popular 17th century European propaganda aimed at demonizing Caribs as fearsome consumers of human flesh, the more balanced missionary accounts prove that such tales of cannibalism were gross exaggerations.

France in 1763 formally ceded Dominica to the British, who then established plantations around the island and for the next 70 years imported thousands of Africans to provide slave labour.

With the 1779 deportation by the British of the so-called fighting Black Caribs of St Vincent to Central America, Kalinago resistance in the Caribbean came to an end. (See also St Vincent, Honduras, Belize, Guatemala, Nicaragua) On Dominica the Kalinago were increasingly squeezed north onto the least accessible land and shoreline where they remained ignored and economically excluded for nearly a century and a half.

Token recognition

It was not until the arrival of a Bntish Commission in 1893, some sixty years after the abolition of slavery, that any attention was paid by the colonial administration to what remained of the Kalinago (Island Caribs) of Dominica.

They found a dispossessed population forced into distant isolation on just 223 acres of mountainous forestland, with no direct easy access to the sea or other means of providing for themselves. Neither were they able to participate in the colonial economy given their lack of schools, church support, or income.

As a result of their petitions, in 1903 the British colonial administration set aside 3,700 acres of land as a Carib Reserve and arranged for an officially recognized office of Chief (endowed with a six pound annual allowance, ceremonial sash and silver headed staff).

In the long runthis did little to change the factors underlying the exclusion and impoverishment of the Carib population and especially the long held prejudices against them. A significant conflict flared in the 1930s sparked by clashes with the colonial police over smuggling. This led to the shooting deaths of two Caribs and the imprisonment of the Chief.

In 1952 a Carib Council was created as part of a general island-wide reform of local government. This legislation was enhanced at Independence in 1978 with the creation of the Carib Reserve Act. It was also not until the 1970s that a road suitable for motor vehicle traffic was finally constructed through the reserve. Electricity and telephone services arrived in the 1980s.

The lingering discontent was demonstrated in 1991 when Chief Irvince Auguiste announced that Dominica’s Caribs did not wish to be involved in proposed celebrations for the quincentenary of Columbus’s arrival in the Caribbean, stressing the legacy of suffering experienced by the region’s indigenous peoples.

Cultural reassertion

In keeping with the growth of the global indigenous movement, in 1997 members of the Dominica Carib community undertook a historic journey as part of the Carib Canoe Project. This was a voyage of rediscovery through the islands back to the ancestral territories in Guyana. It was conducted using a 35 ft dugout canoe specially constructed from a single giant gommier tree.

The project was a practical demonstration of traditional boat-building and navigational skills and was also aimed at re-establishing Carib identity among Dominican Caribs, rescuing the rapidly eroding culture and establishing links with Carib-Arawakan speaking groups in Guyana. These included the Macussi and Wapishana who have retained some key traditional cultural elements in the areas of crafts and language.

In June 2002 the Government of Dominica ratified the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 169, concerning indigenous and tribal people. This makes the Dominican Caribs the only indigenous and tribal people in the English-speaking Caribbean region who can make use of this international instrument.

Current issues

One of the major issues facing the indigenous Kalinago (Carib) in Dominica is the continuing encroachment on their territory by farmers in those zones where the reservation boundaries are still not clearly delineated since the original 1903 land grant. Moreover the increasing population density within the community itself, reduces the availability of viable land.

Another issue facing the population is difficulty in obtaining bank financing. Since all Carib Territory land is communally held, individuals seeking loans are unable to use land as collateral.

Given the ancient Carib ancestral connection to the Orinoco region of the South American mainland (today Guiana-Venezuela), Dominica’s indigenous Carib-Kalinago are likely to have a favourable view of any pan-regional initiative such as ALBA that specially involves indigenous populations and can help to address some of their concerns. For example some programs emerging from Dominica’s membership in ALBA are aimed directly at helping the country’s Caribs. The Venezuelan government is offering $4.5 million to construct housing and a school on Indigenous Carib-Kalinago territory. An agreement has also been reached to establish a credit scheme that will provide $3.2 million in small loans to Carib-Kalinago community members, many of whom are involved in agriculture.

One of the major sources of conflict in Carib areas has been building ownership. Since permits for home building within the territory are issued by the council and are only available to Caribs, those Carib-Kalinago women who are married to, or live with, non-Carib men are often advised to register the property in their own names.Until 1979 the Carib Act allowed only Carib men who were married to non-Caribs to continue living in the Territory. In contrast it dictated that Carib women married to non-Caribs had to move away. The law was changed but it is not yet reflected in practice. An estimated 25 per cent of the Carib-Kalinago population is believed to be in mixed marriages or relationships. Many of these individuals no longer live in the territory which diminishes the opportunity of their offspring to self-identify as Kalinago descendants or become more familiar with their ancestral heritage. This is a significant factor since many key aspects of Carib culture traditionally have been passed on by women. Of the roughly 4,000 people who live on the reserve less than 100 are considered to be (so called,) “full-blooded.”

In May 2008 the Chief of the Dominican Caribs proposed a law requiring ethnic Kalinagos to marry each other exclusively supposedly for reasons of ethnic self-preservation. Chief Charles Williams who is himself of mixed descent argued that outlawing marriage of Caribs to non- Carib outsiders is the only way to save Dominica’s dwindling indigenous population. He also requested that non-Caribs be barred from living on the nearly 3,800-acre Carib reserve.

Several legislators refused to entertain the unprecedented law and according to Associated Press reports, Kent Auguiste, a member of the Carib Indian council which oversees the reserve, while very much in favour of cultural preservation countered that it should not occur at the expense of individual freedoms. There is still a need to deal with the negative and denigrating stereotype of the island Caribs which has a 17th century origin. Many school textbooks and documents in the Caribbean still perpetuate the myth of Carib cannibalism even though experts agree there is little historical evidence to support this. Furthermore the myth continues to have echoes in international popular culture.

The Carib-Kalinago population in Dominica is especially bothered by the depiction of the Carib elements in the movie as slapstick clowns who are playing at being cannibals. However given the small numbers of Carib descendants who are still in the Caribbean and their lack of international influence, Dominica Kalinago do not hold out much hope that their protests will affect future production efforts or change the erroneous stereotype.

Related content

Reports and briefings

-

1 July 1987

The Amerindians of South America

For over 20,000 years a wealth of many cultures flourished in South America, both in the high Andean mountains and the lowland jungles and…

-

1 April 1984

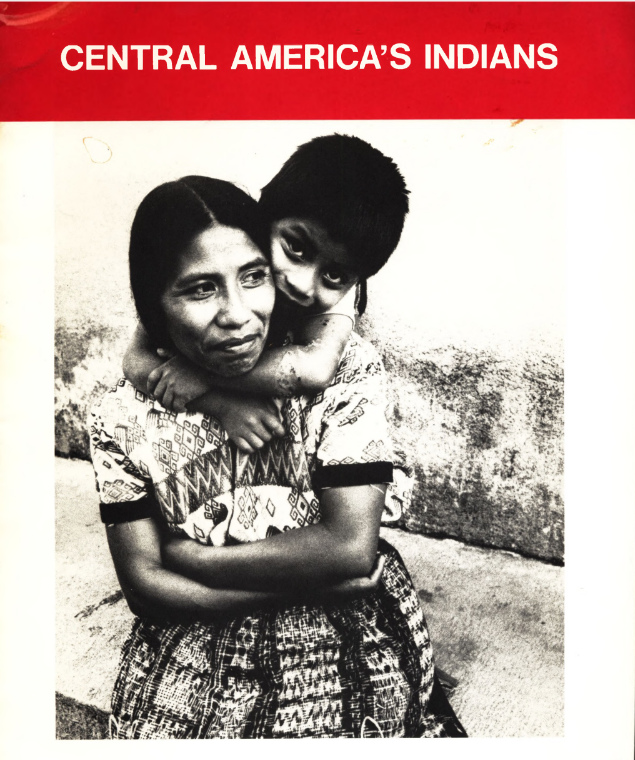

Central America’s Indians

In Latin America today we find one of the largest remnants of colonialism in the world. The concept “Indian” itself is, of course, a…

-

Our strategy

We work with ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, and indigenous peoples to secure their rights and promote understanding between communities.

-

-